Conducting a systematic review

Insights into systematic review methodology, considering which search engines to use, how many to use, and choosing the search terms.

When looking for articles on a particular subject, search engines can quickly produce a wealth of information at our fingertips: 15,400 results in just 0.1 seconds in the search below. In this post I explore the challenge of using search engines to find as much useful literature as possible, whilst not spending all day (or in this case, several months) doing it!

During my PhD I spent many a happy hour looking through the literature on algorithms to estimate respiratory rate from two signals often measured by wearables: the photoplethysmogram and the electrocardiogram. I wanted to find the best algorithm out there, which I assumed meant trawling through every last bit of literature until I found it. In 2017 we published a systematic review of these algorithms, and two of the lessons I learnt stick with me:

- Not all search engines are created equal

- One search engine just isn’t enough (but how many are?)

- You need lots of search terms (but if you’re not careful you’ll get lots of junk)

In the rest of this post I provide insights into these two dilemmas, drawing on the results from our systematic review.

Not all search engines are created equal

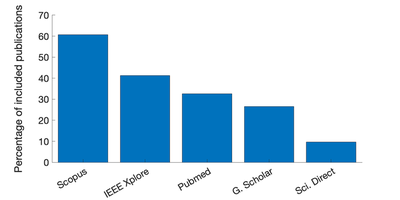

In our review we used five search engines, and our own manual searching, to find the 196 publications included in the review. The five search engines returned vastly different proportions of the 196 publications that were eventually included:

At one end, Scopus returned 61% of the publications (119 out of the 196 included publications). At the other end, Science Direct returned only 10%.

Take home message: A single search engine probably won’t return all the results of interest.

You may also be interested in how much time it takes to download the results from each search engine. In our review we downloaded the results as text files from four of the search engines, and manually copied out the results for one search engine:

| Search Engine | Method used to download results |

|---|---|

| Google Scholar | Copied by hand as no convenient method was available to download results |

| IEEE Xplore | Downloaded as CSV (comma-separated values) file |

| Pubmed | Downloaded as CSV (comma-separated values) file |

| Science Direct | Downloaded as .bib (Bibtex) file |

| Scopus | Downloaded as CSV (comma-separated values) file |

Take home message: Some search engines allow you to easily download the results, others don’t.

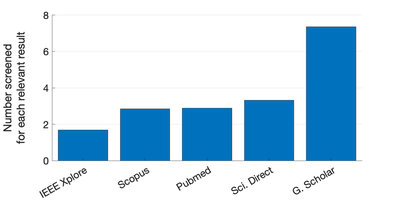

Once you have your results, you then need to screen them to identify the relevant publications for inclusion in the review. This can be time-consuming, so ideally you wouldn’t want to have to screen too many publications for each one finally included. The number of publications we screened per relevant result also varied greatly between search engines:

Take home message: The time taken to screen results varies greatly between search engines.

If you must use only one search engine, choose well, as their performance and ease of use differ greatly.

One search engine just isn’t enough (but how many are?)

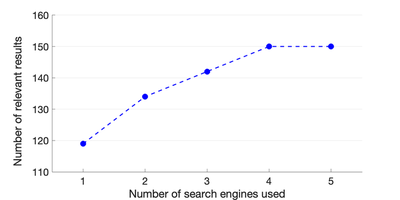

The most comprehensive results came from Scopus, which found 119 out of the 196 publications, but if we’d only used that then we’d have missed nearly 40% of the articles we were looking for. So, one search engine just isn’t enough …

But how many are? Google Scholar returned a huge 383 potentially relevant results, which were copied down by hand (as they couldn’t be exported). In the end, only 14% of these were relevant (it took a while to find that out). At this rate, I wasn’t keen to add more search engines in to the mix. I looked back at how many results we would have obtained when using different numbers of search engines:

So how many search engines are enough? In this search there was some benefit to increasing the number of search engines from one to four, but there was no benefit to using a fifth search engine. You’ll note that even all the search engines together returned only 150 out of 196 of the relevant publications included in the review: the remainder were identified manually (through web searching and reading the literature).

Take home message: It is advisable to use several search engines alongside manual searching.

You need lots of search terms (but if you’re not careful you’ll get lots of junk)

In this review we aimed to obtain as many relevant results as possible from search engines, whilst minimising the amount of work required to screen the results. This meant choosing the search terms carefully. To do so we:

- Performed an initial manual search: this identified 90 relevant publications, which were mostly already known to us.

- Identified key themes from publication titles: we reviewed the titles of these 90 publications to identify three key themes contained within the titles:

- the process of respiration (e.g. breathing)

- a mathematical process (e.g. algorithm)

- the input signal (e.g. photoplethysmogram)

- Identified keywords for each theme: we identified keywords corresponding to each theme which occurred in at least 5% of titles. We found:

- 3 keywords for ‘‘the process of respiration’’

- 15 keywords for ‘‘a mathematical process’’

- 9 keywords for ‘‘the input signal’’

- Eliminated keywords which did not add value: we then looked at the proportion of publications which would have been identified had we insisted on the titles containing at least one keyword from each theme (76.7%). We then eliminated 10 keywords which, individually, did not add value to this search.

- Finalised the search strategy: The final search strategy, which encompassed 75.6% of the 90 manually identified publications was to insist on a publication containing at least one of the following keywords for each theme:

| Theme | Keywords |

|---|---|

| respiration | breathing, respiration, respiratory |

| mathematical process | derivation, derived, estimation, extraction, methods, rate, rates |

| input signal | ECG, electrocardiogram, photoplethysmogram, photoplethysmographic, photoplethysmography, PPG, pulse |

The end result was that our search identified 642 publications, 31% of which were deemed to be relevant, leading to the 196 publications which were finally included.

Take home message: Choose keywords carefully to avoid getting too much junk.

If you are interested to find out more then you can read the review here.

Acknowledgment

Some of the content for this post was adapted under the CC BY 3.0 Licence from:

P. H. Charlton et al., ‘'Breathing rate estimation from the electrocardiogram and photoplethysmogram: a review,’' IEEE Rev. Biomed. Eng., vol. 11, pp. 2-20, 2018.

Appendix: reproducing the results

This appendix describes how to reproduce the results described and illustrated in this blog, and also the results presented in the review paper. NB: You will need Matlab software to reproduce these results. The files required are available at: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3741463 .

Optimising the search strategy

The BRLitReviewSearchStrategy.m script reproduces the analysis used to optimise the search strategy, and generate the search strings.

Conducting the search

See the _BR_lit_review_suppl_mat.pdf file (Section S1.D) within the article’s supplementary material for details of how to reproduce the search.

Analysing the search results

Run BRReviewAnalyses.m to obtain:

- The screening process results (as described in the BR_lit_review_suppl_mat.pdf file (Section S1.C) within the article’s supplementary material).

- The plots in this blog

- The results of the analysis of individual articles

You will also need the BRReviewScreeningResults.xlsx and BRReviewMethodologiesData.xlsx files to reproduce these results.